This article was co-authored by Pablo Garcia Quint, a Tech and Innovation Policy Fellow at Libertas Institute.

The fear that technology will “kill jobs” is nothing new. If anything, it’s overplayed and worn out. When we look back, big technological shifts haven’t wiped out the drudgery we call work without also creating a ton of fresh new “opportunities.” And certainly not at the speed and scale that justifies decades of expert-driven technopanic – sometimes also referred to as “work addiction.”

In the 1960s, Americans feared automation so much that it made the cover of LIFE magazine. And now, we’re picking up where we left off with the advent of Artificial Intelligence (“AI”).

But if we zoom out, it’s quite clear that these disruptions to the traditional workplace have never led to a jobless society or a lower standard of living. Quite the opposite. Tech revolutions have coincided with cheaper goods, better jobs, and rising standards of living. Setting aside the fact that we still have to work, that’s a pretty good deal. Understanding the reasons behind this pattern of progress is the only way to avoid drawing a premature conclusion about the effect of new technologies we’re encountering today, and even that which we will encounter in the future.

Displacement ≠ Decline

Job loss, referred to by economists as “displacement” may be an inevitable consequence of new technology, but those economists tell us that figuring out who, exactly, is affected depends largely on the types of jobs involved, the skills workers possess, and the technological breakthroughs humanity achieves.

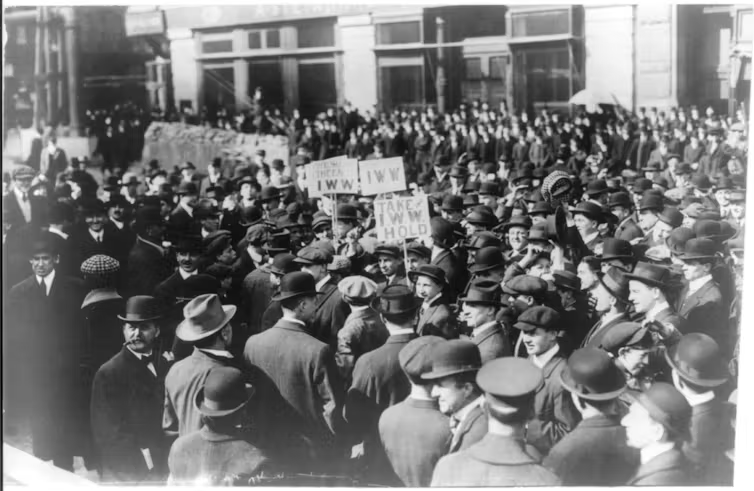

Still, when displacement does occur, it rarely goes unaddressed. Historically, we’ve seen efforts from the federal government and state governments to create a range of job training programs for displaced workers in times of rapid technological change.

While these programs certainly deserve credit for helping to ease some of the unemployment caused by new technology, this doesn’t account for all that happened to prevent the historical trends of major technological revolutions from kicking off a chain-reaction of mass societal decline. The other side of the equation is the positive effects of technology.

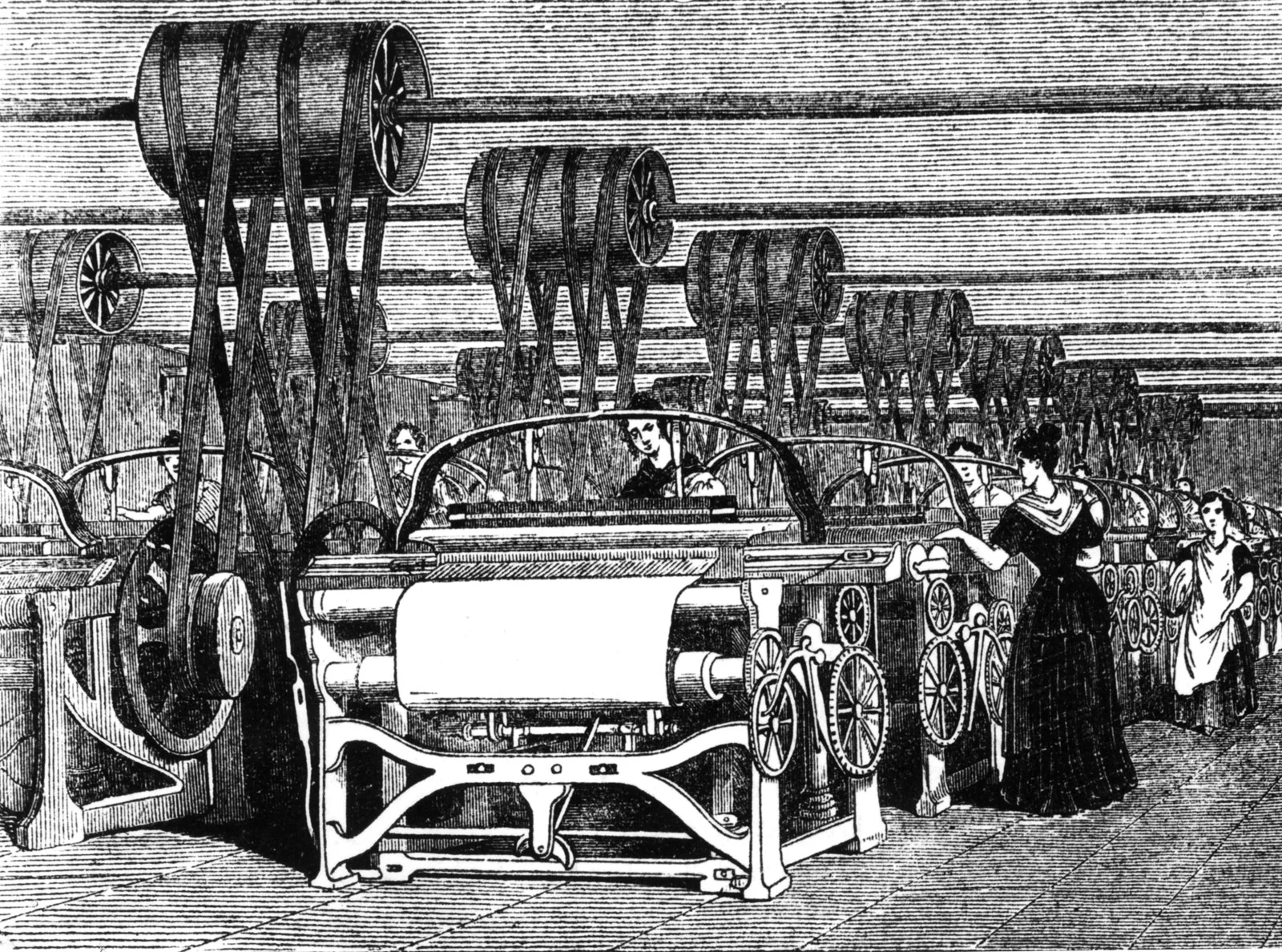

Technological advancements often make workers more productive than before. Yes, it doesn’t affect all industries equally, but it transforms them so they can produce more with less – or as the economists put it, higher outputs with fewer inputs.

Farming is a great example of this. In the early 20th century, nearly half of Americans worked in agriculture. Today, it’s less than 2%. Yet unemployment still hovers around 4-7% on average, food is more abundant, more affordable, and more widely available than ever. Economist Marian Tupy showed that among many trends in the agricultural sector, grain production exploded, hunger plummeted, and protein intake rose. All of these signs were of abundance, not decline.

Predicting the future of the agricultural sector at the moment machines started to play a bigger role in agriculture would have had a dire outcome, but ultimately, it would have been mistaken.

The automobile industry is another great example. As Ford rolled out the Model T, its price dropped from $950 in 1909 to $440 in 1915, thanks largely to a shift from labor-intensive manufacturing to the assembly line-enabled “capital-intensive” manufacturing. This made cars affordable for middle-class Americans, fueling demand and giving rise to entirely new industries from highways to motels, and creating jobs in areas that hadn’t existed before. Over time, the physical dangers of factory work declined. The economy gradually shifted toward a service-oriented economy, and gains in productivity translated into higher wages and lower costs.

The same playbook was repeated in computing. Once a sector with limited labor demand, the technology sector saw both job growth and the creation of entirely new roles as new devices and innovations emerged. In a little over 10 years, from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s, over a million more jobs were created in roles that did not exist before – database administrators, cybersecurity pros, and network architects, among others. With it, the price of devices such as smartphones and computers became more accessible, and the computational power became better and cheaper too.

This dynamic has repeated across many other sectors. Manufacturing, transportation, and communication have all undergone significant automation, but in each case, the initial fears of widespread unemployment gave way to a broader economic expansion.

Sure, AI will disrupt lots of things. But if history is any indication, AI will also open doors, drop prices, raise productivity, and build a better future. History shows that technological change is more often a catalyst for abundance, and unfortunately, none of us are done working just yet.